CLINICIAN

The rugby team warm-up historically consists of 30-40mins of low to high intensity exercise. One would typically see a jog around the pitch followed by some type of stretching and some grid drills before the players split off to do some lineouts (forwards) or some passing patterns and kicking (backs) before coming together and returning to changing room or standing in a huddle. There has been suggestion that this is not optimum for a 60-80min game of repeated anaerobic exertion and recovery (Taylor, Weston, & Portas, 2013; van den Tillaar & von Heimburg, 2016; Zois, Bishop, Ball, & Aughey, 2011)

So what is a warm up, what does it aim to achieve and what should it look like?

Warm –up: The act of preparation to optimise proceeding exercise or physical competition

This general statement whilst being simple encompasses all the facets of preparedness without being prescriptive which means no restrictions or recipes.

This review will attempt to demystify physical preparation ‘warm up’ for the rugby team. It will look at the physiological processes required and will critically analyse current warm up concepts and steer you towards a more efficient process.

So we understand the goal what processes need to occur to bring us to a solution?

An active warm up is more likely to provide the preparedness required for playing a game by enabling the physiological changes required. Our first concern is to increase muscle and core temperature (Bishop, 2003). An elevation in these may enhance cellular metabolism and make more energy available for work. As rugby union is a UK winter sport and changing rooms are often unheated it is of importance to maintain this higher core temp between warm up and the start of play.

A higher core temperature is associated with a higher metabolic rate (Landsberg, Young, Leonard, Linsenmeier, & Turek, 2009) although this seems to have limited effect on endurance type exercise (A. M. Jones, Koppo, & Burnley, 2003) which rugby – despite having high intensity bursts of anaerobic activity, essentially is. Warm up activity does seem to improve ATP turnover during the first few minutes of play (Gray, Soderlund, Watson, & Ferguson, 2011). This can enable domination of the game from the start. This is important tactically and mentally early on in invasion games. It does seem more elite athletes may need more intensity whilst the less able will have relatively quick temperature increases at a lower intensity. Increasing temp can also increase time to fatigue (Bergh & Ekblom, 1979).

An increase in muscle temperature has been shown to elicit a greater peak maximal power with further pyrexia related to an earlier rate of fatigue (Sargeant, 1987). The increase can also improve nerve conduction velocity and subsequent muscle contraction. This would be of use in the contact area and sprinting with predominantly fast twitch activation. If the ambient temperature is comparatively high there could be a further increase in core temperature that could necessitate increased demand for skin blood flow to enhance thermoregulation. There is surprisingly not a corresponding decrease in blood flow to the muscles but an upper core temp of 40 degrees Celsius appears to decrease muscle metabolic rate via falling blood pressure due to central control of cardiac output (González-Alonso, Crandall, Johnson, & González-Alonso, 2008). This is not as likely in rugby but in this situation (e.g. middle eastern games and tournaments) pre game preparation could include decreasing of core temp with cooling strategies (Price, Boyd, & Goosey-Tolfrey, 2009). This will not be dealt with in this review but in fact ambient temperature must be a consideration when planning a warm up.

As the muscles begin to contract they will require increased oxygen and blood will be diverted from inactive muscles and some organs to skin active muscles and myocardium. There is a small period of time where demand for oxygen will outstrip supply. It is important this mismatch is addressed during the warm up before the game starts. Vascular conductance is increased at this time to avoid compromising blood pressure. There will be a drop in performance until this is rectified by reaching VO2 max (González-Alonso et al., 2008).

In conclusion when considering bioenergetics the warm up should aim to increase core temperature enough to optimally increase VO2 but not enough to boost it to thermoregulatory strain where muscle metabolism will decrease. Zois et al (2011) believes this should be between 5-10 minutes but no longer. The player must hit VO2 max as quickly and for a short time as or glycogen in the muscle may be depleted (Bishop, 2003) it is also thought maintenance of power output during high-intensity intermittent exercise is limited by depletion of phosphocreatine (PCr) stores so it is important to keep those as full as possible.

The increased VO2 may also allow some anaerobic capacity to be retained into the game. After warm up to 15 minutes is required to almost fully recharge cellular PCr but at least 5 minutes is required to top-up (Sahlin, Harris, & Hultman, 1979). The 15 minutes is slightly at odds with core temp which needs to be maintained. In the event of very cold weather suitable heat retaining garments could be worn at this time (Raccuglia et al., 2016).

Beyond bioenergetics it is thought that some type of game specific movements can ergogenically aid performance with the use of post activation potentiation (PAP) so maximal or submaximal squats, leg press etc. with a prescribed rest period before activity. It is not clear from the literature if this can aid force production beyond a short term performance such as sprint, maximum jump or lift but there may be some carry over (Maloney, Turner, & Fletcher, 2014; West et al., 2016). It may be that large compound explosive, high intensity contractions allow motor unit priming without causing excessive PCr depletion and lactate production (C. Jones, 2003).This area of research still has much to discover. Barnes, Hopkins, McGuigan, & Kilding (2015) suggested 6x 10s strides with a small weight improved leg stiffness and running economy for endurance sports. West (2016) went further and looked at repeat sprint ability which is key for most invasion games. He used 5 sets of 3 counter movement jumps and passive heating but during the time between warm up and game. In rugby union it could be practical to pair up and 3 sets of 5 hitting a tackle bag off the floor. High intensity of short duration for the forwards.

Injury prevention is another aim of warm up but so far it has been difficult to measure any effects on this variable. Alsop et al (2005) found no correlation between warm up and injury and to date the biggest injury predictor is still work load spike (Hulin et al., 2013). So it may be that warm up is purely useful for optimum performance.

There are other techniques that have been found to aid warm up and others that must be discarded.

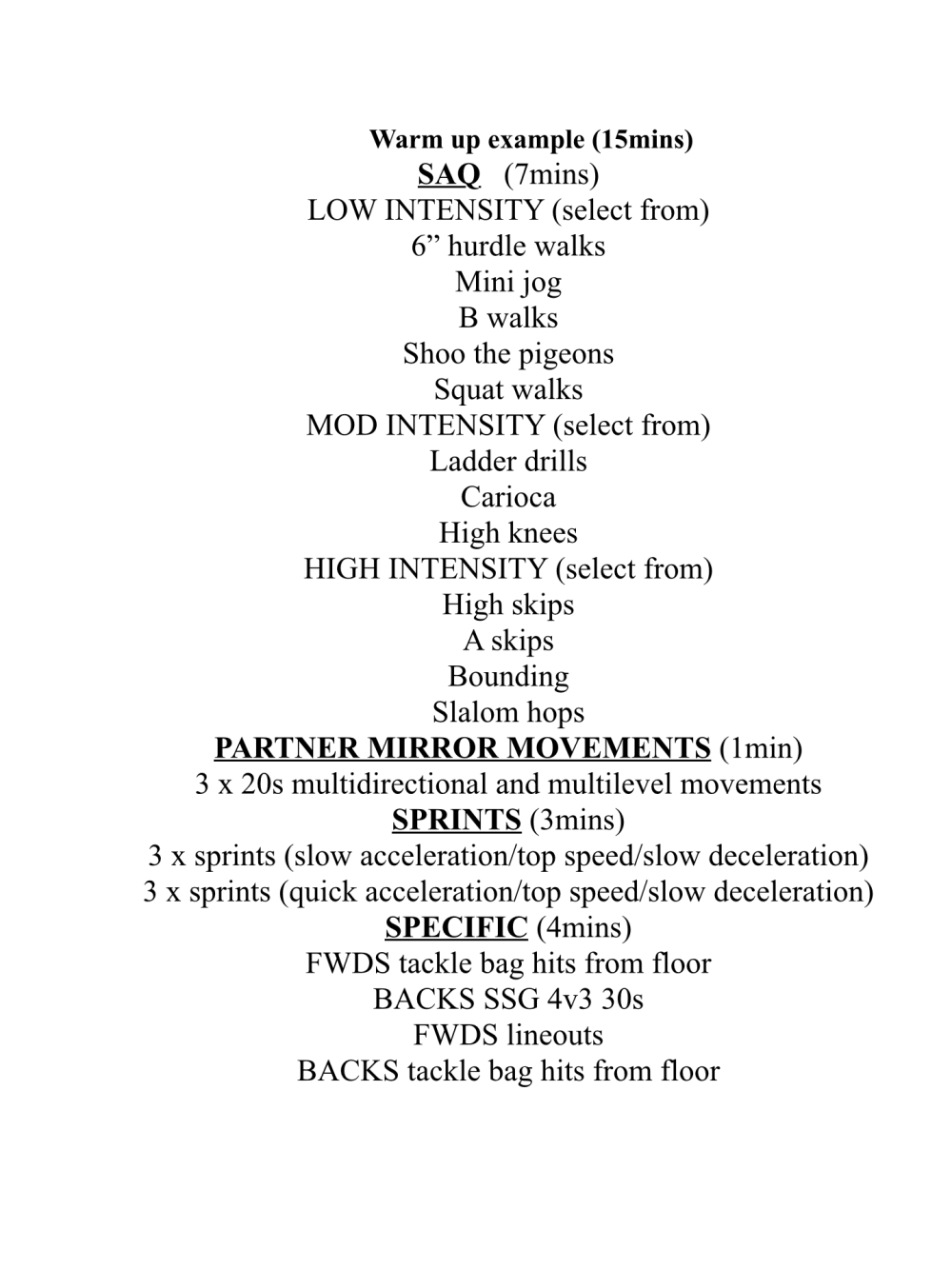

SAQ

Polman, Bloomfleld andEdwards (2009) compared small sided games (SSG) with speed agility and quickness drills (SAQ) in untrained subjects. He found SAQ improved sprint performance and strength. Of course this could be due to the less complex nature of the SAQ drill in comparison to the SSG. More elite athletes may be more competent in playing SSG and may achieve greater priming.

FOAM ROLLING

Foam rolling does not enhance any performance markers as a warm up technique. However, it is a popular warm up tool and does not appear to cause any detriment to the athlete so if they like it there is no harm providing it is not taking the time of something more useful (Healey, Hatfield, Blanpied, Dorfman, & Riebe, 2014)

MUSCLE ACTIVATION (PRIMING)

There is some evidence that gluteal activation (15 reps plus) leads to enhance sprint speed (Barry, Kenny, & Comyns, 2016). Skof and Strojnik (2007) found Bounding and sprinting contributed to the power and anaerobic warm up of the system and potentiation of the contractile complex.

STATIC STRETCHING

Static stretching decreases sprint performance and explosive activity in many studies (Fletcher & Jones, 2004; Gelen, 2010; Sim, Dawson, Guelfi, Wallman, & Young, 2009; Simic, Sarabon, & Markovic, 2013) and dynamic stretching sprint performance in some participants (Fletcher & Jones, 2004). It is not recommended for warm up. Despite this stretching is an incredibly popular pre exercise adjunct.

POWER BREATHING

Inspiratory muscle activity does not affect performance and power breathe should not be used during warm up (Ohya, Hagiwara, & Suzuki, 2015)

PRE PERFORMANCE MASSAGE

Massage negatively affects isokinetic performance and probably should not be incorporated (Lawrence, 2011)

POST WARMUP PRE GAME HEATING

(Sargeant, 1987) found for every 1 degree Celsius of cooling post warm up there is 3% decrease in muscle power which could directly affect explosive activity once the game starts. It may be that heating maintains neuro-motor pathways or because glycolysis and hydrolysis of PCr is increased there is improved ATP availability, but this is not proven.

So to return to our remit. What makes a good warm up?

· Increased VO2

· Optimum warm core and muscle temperature

· Not > 15mins (to avoid fatigue)

· Primed large muscle groups

References

Alsop, J. C., Morrison, L., Williams, S. M., Chalmers, D. J., & Simpson, J. C. (2005). Playing conditions, player preparation and rugby injury: A case-control study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 8(2), 171–180.

Barnes, K. R., Hopkins, W. G., McGuigan, M. R., & Kilding, A. E. (2015). Warm-up with a weighted vest improves running performance via leg stiffness and running economy. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(1), 103–108.

Barry, L., Kenny, I., & Comyns, T. (2016). Performance effects of repetition specific gluteal activation protocols on acceleration in male rugby union players. Journal of Human Kinetics, 54(1), 33–42.

Bergh, U., & Ekblom, B. (1979). Physical performance and peak aerobic power at different body temperatures. Journal of Applied Physiology, 46(5).

Bishop, D. (2003). Warm up II: Performance changes following active warm up and how to structure the warm up. Sports Medicine, 33(7), 483–498.

Fletcher, I. M., & Jones, B. (2004). The Effect of Different Warm-Up Stretch Protocols on 20 Meter Sprint Performance in Trained Rugby Union Players. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(4), 885.

Gelen, E. (2010). Acute Effects of Different Warm-Up Methods on Sprint, Slalom Dribbling, and Penalty Kick Performance in Soccer Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(4), 950–956.

González-Alonso, J., Crandall, C. G., Johnson, J. M., & González-Alonso, J. (2008). The cardiovascular challenge of exercising in the heat. J Physiol, 5861, 45–53.

Gray, S. R., Soderlund, K., Watson, M., & Ferguson, R. A. (2011). Skeletal muscle ATP turnover and single fibre ATP and PCr content during intense exercise at different muscle temperatures in humans. Pflugers Archiv European Journal of Physiology, 462(6), 885–893.

Healey, K. C., Hatfield, D. L., Blanpied, P., Dorfman, L. R., & Riebe, D. (2014). The Effects of Myofascial Release With Foam Rolling on Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), 61–68.

Hulin, B. T., Gabbett, T. J., Blanch, P., Chapman, P., Bailey, D., Orchard, J. W., & Gabbett, T. (2013). Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers. British Journal of Sports …, 0, 1–5.

Jones, A. M., Koppo, K., & Burnley, M. (2003). Effects of Prior Exercise on Metabolic and Gas Exchange Responses to Exercise. Sports Medicine, 33(13), 949–971.

Landsberg, L., Young, J. B., Leonard, W. R., Linsenmeier, R. A., & Turek, F. W. (2009). Do the obese have lower body temperatures? A new look at a forgotten variable in energy balance. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 120, 287–95.

Lawrence, D. J. (2011). Effects of pre-performance massage before isokinetic exercise. Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 16(3), 246–247.

Maloney, S. J., Turner, A. N., & Fletcher, I. M. (2014). Ballistic Exercise as a Pre-Activation Stimulus: A Review of the Literature and Practical Applications. Sports Medicine, 44(10), 1347–1359.

Ohya, T., Hagiwara, M., & Suzuki, Y. (2015). Inspiratory muscle warm-up has no impact on performance or locomotor muscle oxygenation during high-intensity intermittent sprint cycling exercise. SpringerPlus, 4(1), 556.

Polman, R., Bloomfleld, J., & Edwards, A. (2009). Effects of SAQ training and small-sided games on neuromuscular functioning in untrained subjects. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 4(4), 494–505.

Price, M. J., Boyd, C., & Goosey-Tolfrey, V. L. (2009). The physiological effects of pre-event and midevent cooling during intermittent running in the heat in elite female soccer players. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 34(5), 942–949.

Raccuglia, M., Lloyd, A., Filingeri, D., Faulkner, S. H., Hodder, S., & Havenith, G. (2016). Post-warm-up muscle temperature maintenance: blood flow contribution and external heating optimisation. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 116(2), 395–404.

Sahlin, K., Harris, R. C., & Hultman, E. (1979). Resynthesis of creatine phosphate in human muscle after exercise in relation to intramuscular pH and availability of oxygen. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation, 39(6), 551–557.

Sargeant, A. J. (1987). Effect of muscle temperature on leg extension force and short-term power output in humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 56(6), 693–8.

Sim, A. Y., Dawson, B. T., Guelfi, K. J., Wallman, K. E., & Young, W. B. (2009). Effects of Static Stretching in Warm-Up on Repeated Sprint Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(7), 2155–2162.

Simic, L., Sarabon, N., & Markovic, G. (2013). Does pre-exercise static stretching inhibit maximal muscular performance? A meta-analytical review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 23(2), 131–148.

Skof, B., & Strojnik, V. (2007). THE EFFECT OF TWO WARM-UP PROTOCOLS ON SOME BIOMECHANICAL PARAMETERS OF THE NEUROMUSCULAR SYSTEM OF MIDDLE DISTANCE RUNNERS. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(2), 394–399.

Taylor, J. M., Weston, M., & Portas, M. D. (2013). The Effect of a Short Practical Warm-up Protocol on Repeated Sprint Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(7), 2034–2038.

van den Tillaar, R., & von Heimburg, E. (2016). Comparison of Two Types of Warm-Up Upon Repeated-Sprint Performance in Experienced Soccer Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(8), 2258–2265.

West, D. J., Russell, M., Bracken, R. M., Cook, C. J., Giroud, T., & Kilduff, L. P. (2016). Post-warmup strategies to maintain body temperature and physical performance in professional rugby union players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(2), 110–115.

Zois, J., Bishop, D. J., Ball, K., & Aughey, R. J. (2011). High-intensity warm-ups elicit superior performance to a current soccer warm-up routine. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 14(6), 522–528.

.